SEDUCE & CONQUER | How an invasive tree divides farmers and gobbles up land in Kenya

A grim sight lay ahead.

It was nearing mid-day, the sun ablaze.

We walked carefully past the goat pen, treading over thorny weeds.

*WARNING: this video contains scenes that may be disturbing to some viewers*

THE FATAL SWEETNESS OF PROSOPIS FRUIT

Rispah Enenganai’s goat had perished earlier that morning.

Her neighbour’s goat also died that day. And they knew the culprit all too well.

This is what happens to animals feeding on fruits from Prosopis juliflora, a shrub-tree species that grows everywhere in this part of Kenya and is known locally as mathenge. The fruit is seductively sweet—so delicious, they can’t get enough. But feasting on it sets off a deadly chain of events.

Goats and cows simply can’t cope with Prosopis. As semi-digested fruits or pods get stuck inside the animal’s gut, they solidify into a block. No food or water can get through, and digestion gets disrupted. When the animals try to feed on grass, their body reacts by producing a green discharge that leaves them dehydrated.

The problems multiply once an animal succumbs to the fruit’s sweetness. Eating the sugar-rich pods softens the teeth to a point where they drop off one by one. The mouth shakes uncontrollably, jaws sliding from side to side, making it ever harder for the animals to eat or drink.

Over a short period of time—a matter of days—the animals waste away. By the time farmers notice a problem, it’s usually too late.

Rispah Enenganai, farmer“Mathenge has been a nightmare for many years. There is no hope for us or the goat when symptoms appear. The goat dies a silent death within days.”

(Il Chamus ethnic group)

A THORNY PROBLEM

Prosopis has been gaining ground in East Africa for decades, and its territory is still expanding at pace.

It comes with a long list of problems that aren’t limited to fatally sweet fruit.

The branches ofP. julifloratrees are full of large sharp thorns that injure farmers as they go about managing their land. The spikes deform fish in nearby Lake Baringo, damage fishing nets, and puncture vehicle tyres.

A shrubby tree, this Prosopis species spreads out so thick that waterways, roads and trails become difficult to access. Along the way, vast quantities of water are sucked up from the ground, aggravating impacts of climate change in this dryland area.

Once the invasive species takes hold, it’s very hard to get rid of it.

In part, that’s because of how resilient it is and how easily it spreads.

New shrubs will grow wherever mature fruit falls from a mature tree and the pods split, releasing seeds into the ground. But P. juliflora can easily travel farther afield.

Young children enjoy the pods as a tasty snack, taking the sweet juice before they spit out the seeds—where those seeds land, the shrubs grow. Monkeys eat the fruit too, helping the spread in much the same way. When livestock expel the seeds in their droppings the dung acts like fertiliser, making it even easier for new shrubs to grow. In a land of pastoralists, where animals move from place to place, it’s easy to plant new shrubs across a distance. Water from heavy rains can also carry seeds a long way.

Because of how P. juliflora replants itself over and over, it cannot be completely eradicated. The only way is to control it. But cutting down the shrub is hard work, doesn’t come cheap, and can only go so far for a species that grows back fast.

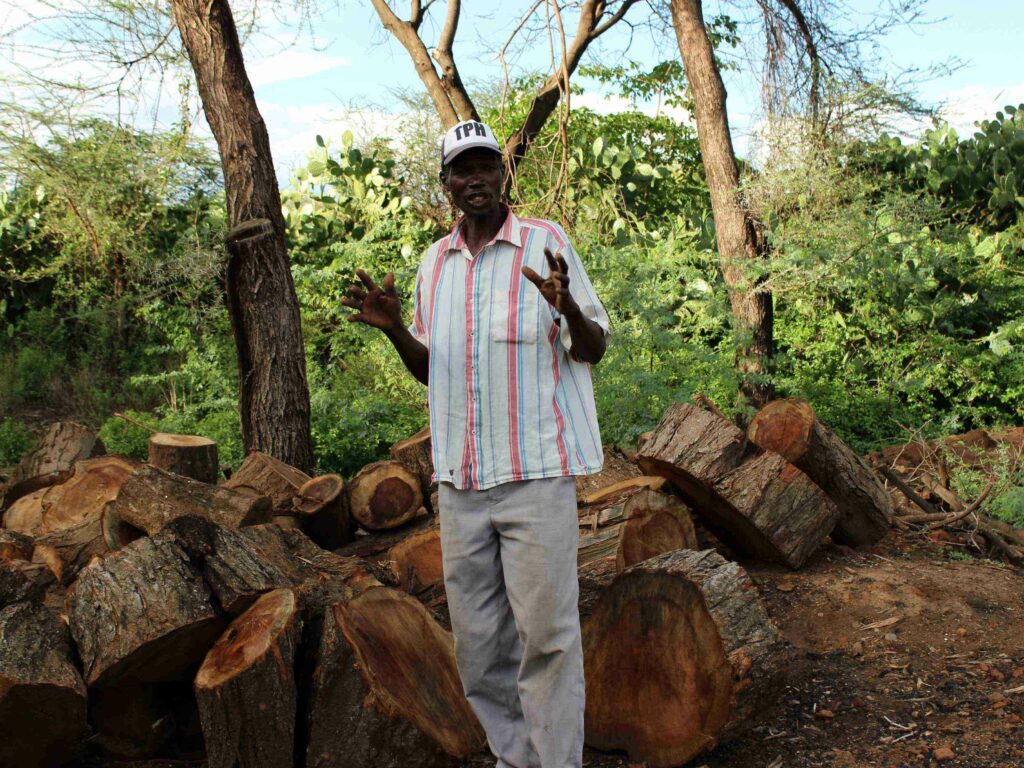

Stuck with the omnipresent tree, people in this part of Kenya often try to reap some benefits: the wood can be burnt for fuel. It’s used as a building material, to build fences for example. And it’s burnt to make charcoal. Even so, surveys suggest that most residents of Baringo believe they would be better off without Prosopis.

“You clear Prosopis until it depletes your resources.”

Jane Parsalach, farmer

(Il Chamus ethnic group)

“I don’t need that kind of tree again.”

Pauline Chelagat (Tugen ethnic group)

SHARED TERRITORY, COMMON ENEMY

Jane Parsalach belongs to the II Chamus ethnic community. Pauline Chelagat is a Tugen.

Il Chamus and Tugen are two ethnic groups facing a common enemy in the invasive species.

The area being gobbled up by P. juliflora in this part of Baringo country is made up of mostly communal land. It is home to several pastoral groups which then end up competing for resources, moving ever closer to the edge of their respective territories.

Where land is used for crop production the shrub isn’t much of a problem. But it takes hold easily where land sits idle, and the usable area soon begins to shrink. All grasses disappear once Prosopis takes over more than half the rangeland in a particular area. That’s a worst-case scenario for grazing livestock, which local people rely on for their livelihood. And as invasions eat into common territory, it gets easier for conflict to flare up.

Community leaders Samwel Montorosi, from the Il Chamus ethnic group, and Jonathan Mitei, from the Tugen ethnic group, are well aware of the damage—and they’re open to solutions that compensate for that damage.

“Some of the strong Prosopis…can damage engines, and that is another challenge to be costed.”

Samwel Montorosi, chairman of Baringo CPA (Il Chamus ethnic group)

“We can produce charcoal in a way of compensation for the community.”

Jonathan Mitei, chairman of Lokasacha CPA (Tugen ethnic group)

A BATTLE PLAN ROOTED IN RESEARCH

How do you solve a problem like Prosopis?

Rooting out this invasive species takes science, sound policies, community action—and persistence.

According to Simon Choge, Principal Research Officer at KEFRI, the tree was brought to this part of the world around 1950 from South Africa. Intentions were good: Prosopis can withstand harsh conditions, stabilise soils and provide firewood. But some species do more harm than good.

After the mid-1970s, the population of harmful Prosopis simply exploded. Spreading far and wide, it displaced everything else on its path: pasture, grasses—it’s all gone when the tree conquers the land. It first moved along rivers, then on to road networks and irrigation canals.

The amount of land taken over in this region spiked by more than 2000% over nearly 30 years, making Baringo county one of the most heavily invaded areas of eastern Africa. Researchers estimate that, left unchecked, 80% of land in this part of Baringo will be lost to Prosopis in coming years.

Low-income countries often lack enough capacity and resources to tackle the problem. To support control efforts in this part of the continent, a research team started work in 2015 through Woody Weeds, a project led by Urs Schaffner, head of Ecosystems Management at CABI Europe-Switzerland, and supported by the r4d programme—a joint initiative by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and the Swiss National Science Foundation. One of the first steps in this work was to research different management options, and what they could mean for local people and the environment.

The project also helped shape Kenya’s first national strategy to tackle Prosopis. First put to the test in Baringo county, the strategy attacks the problem with proposed actions on various fronts:

- Introducing insects to reduce seed production.

- Applying chemicals at the point of cutting a Prosopis tree to stop regrowth.

- Physically removing the trees, e.g. with a bulldozer.

- Planting pasture, or indigenous tree species, on land that would otherwise be taken over by the invasive species.

- Promoting utilisation of the trees—recognising that this generates some income, but also that it does not stop the invasion.

The project initiated a number of activities, including participatory processes to select, test and implement actions to help manage Prosopis, as well as training of local community groups on the various ways to tackle the spread. Communities were also involved in the planning stage of a National Prosopis Strategy, which was signed in late 2022 by Kenya’s Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Forestry.

IN SEARCH OF SOLUTIONS

Tapping into the charcoal market is proving attractive.

One prong of the control strategy—charcoal production—has become an important source of income for local communities.

It took off some 15 years ago, after a policy came in to encourage use of Prosopis to make charcoal in Baringo. The idea was to fight back against spread of the shrub by tapping into the economic benefit of selling charcoal. Could production use up enough of the woody species to make a difference

Government associations were formed to regulate production. There are now 6 Charcoal Producers Associations (CPAs) in Baringo, helping farmers to negotiate a better price and find buyers. Each farmer making charcoal needs to register with a CPA. Once they deliver their product to a collection point, the CPA registers how much is brought in, and the charcoal is sent out for delivery.

CPA leaders say that one lorry can carry some 150 bags, which sell locally at a minimum of Ksh400 (US$3) shillings per bag. A single farmer can produce as many as 30 bags per week, making a generous income for the area.

But in 2020 the government banned charcoal production, acting on signs that tree species other than P. julifrola were being cut illegally to feed the production line.

Meanwhile, charcoal-making continues informally, and one of the CPAs has teamed up with an investor to turn production into a business.

The charcoal trade is helping to boost income in a community that relies on small-scale farming and livestock.

But it isn’t helping the environment.

Part of the proceeds from farmers’ charcoal sales go towards the community, according to CPA leaders, through a percentage deduction from each farmer’s payment into an account that funds development projects. They say the money has already funded sanitation infrastructure in preschools; sponsored school exams for primary schools; and helped set up irrigation schemes to remove silt from canals so community farms can access water more easily.

But when it comes to environmental impact, the research team’s findings are clear and sobering: over those 15 years of charcoal production, using the wood has made no difference to the spread of the invasive tree. This data has helped to sway the government away from a longstanding, contested policy of encouraging local people to use Prosopis wood as a way to manage the trees.

Still, the charcoal market is thriving.

The average city apartment in Kenya doesn’t have a heating system. But unlike people who live in rural areas, city dwellers can’t use firewood in apartment buildings: burning charcoal indoors fills the walls with soot. For most, it’s simply too expensive to cook with electricity or gas. Charcoal is cheaper to use. It only takes a small portion to get the job done—a bag can last for days. Made with the right process, Baringo can produce high-quality charcoal.

Faced with the trade-offs between boosting income in the short term and protecting the environment and livelihoods over the long-term, the community faces the challenge of balancing the good and the bad with effective management.

“Nowadays we don’t take it as something bad, but as a resource.”

Dennis Kipchemoi, farmer and teacher (Tugen ethnic group)

It’s a case of tough trade-offs.

Baringo residents already affected by Prosopis know they have no choice but to live with it. Support from the R4D project has helped them to identify the tree stubs and do something about the problem.

But using up the wood isn’t enough to curb the spread. The scientists know that any solution that fails to remove the hardy shrub by the root means it will keep expanding its territory.

Some 90% of areas in Baringo county are yet to be invaded. But if nothing is done, they won’t stay Prosopis-free. The region at risk goes up to the world-famous Maasai Mara National Park, where the thorny tree could harm wildlife that draws hundreds of thousands of tourists each year.

For communities already affected, the invasive species is forcing a tough choice between environmental and economic priorities. Selling charcoal is an attractive business. Even where modest and small-scale, it brings in immediate cash. And demand for charcoal is on the rise as the price of other fuels skyrockets.

Can local farmers take the pain of losing income in the short-term to beat back the hardy invader in the long-term?

The researchers believe that finding a solution hinges on stepping back to look at the problem across the region, and fighting back the invasion with a strategy adapted to different areas.

For now, raising awareness is the key to persuade people in Baringo and beyond that taking the hard path—turning away the invader’s seductive benefits—is the only real chance to root out Prosopis for good.

Produced by anita makri | words. ideas. Images.

Based on material collected in Baringo, Kenya, in April-May 2022–with thanks to KEFRI and the Il Chamus and Tugen communities.

Anita Makri: story, text and visuals

Joyce Chimbi: local interviews and translation

Supported by the r4d programme – Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development