A drop of vanilla: Finding a way out of Madagascar’s ‘triple crisis’

It was looking like a bad year even before Covid-19 made it to the northeastern tip of Madagascar. The island is the world’s largest vanilla producer, and farmers in this remote area had watched their income dwindle as the price of the delicate spice began a downward spiral in early 2020.

Things only got worse as disruptions caused by the pandemic cut off vital supplies. This is a part of the island accessible mainly by boat or a flight. Local people were simply running out of options to secure basic provisions to last the year.

“There [were] two risks,” says Onintsoa Ravaka Andriamihaja, a land governance scientist at the Centre for Development and Environment, which is affiliated with the University of Bern. “Not having rice to buy, but also not having money to buy rice.”

Andriamihaja spent the past few years travelling across villages in this region for a research project that suggests part of the solution is to understand how use of the land changed over the years, and who influenced these changes.

“It just triggered a new wave of deforestation”

Onintsoa Ravaka Andriamihaja, University of Bern

When the price of vanilla soared from 2016 to 2019, local farmers turned their rice plots into vanilla plantations. Things then changed once again as the Covid-19 pandemic – and the drop in vanilla prices – prompted farmers to turn back to cultivating rice.

The strategy can put food on the table in a matter of months. But it also comes at a cost.“It just triggered a new wave of deforestation,” says Andriamihaja.

In some ways, it’s a lose-lose proposition. By cutting down vanilla plantations, farmers give up a huge investment. When they clear fresh swathes of forest to make way for rice plots, new environmental stress adds to damage done over years of expanding rice and cash crop plantations.

Deforestation, the vanilla price crash and Covid-19 created what the research team calls a “triple crisis”.

But this could also be the right time to lay the foundations for a lasting solution to the conflict between conservation and agriculture, which lies at the heart of efforts to manage land sustainably in this part of Madagascar.

Picture 1:Land cleared for agricultural expansion on the edge of the forest, between Andratamarina village and Beanana village in the municipality of Morafeno.Credit: O. Ravaka Andriamihaja

Unpredictable swings

Unlike the south of the island, where a hunger emergency is unfolding after record levels of drought linked to climate change, rain still falls on northeastern Madagascar. There, food security can change dramatically over the years as farmers’ income relies on cash crop prices that swing unpredictably.

Vanilla is especially important for people in the area, says Bruno Ramamonjisoa, a forest economist at the University of Antananarivo and a member of the project team alongside Andriamihaja and Flurina Schneider, from the Institute of Socio-Ecological Research in Germany. “They can use [income from vanilla] for one year or for two years” he says.

The deforestation that comes with growing the popular spice sets up a standoff between farmers and traders on one side, and those who work to conserve forests on the other. They work on the same stretches of land but hardly ever talk to each other, says Andriamihaja.

A new phase of the project – funded by the r4d programme, a joint initiative by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and the Swiss National Science Foundation – now plans to bring them around the same table in an attempt to spark a conversation.

The hope is that the process will help align their interests, and shape policies that benefit both sides. Current policies that ban agricultural expansion into forest just don’t seem to work.

Cash crops bring in the money. But when the going gets tough in times of crisis, people turn to the forest to make ends meet: cultivating rice offers security. Both the strategies farmers pursue to provide for their families rely on the forest. “They know that even if [the cash crop price is] up today, some time it will go down,” explains Andriamihaja. “So they do not leave totally the rice cultivation, but expand into forests.”

The team is homing in on tackling the insecurity behind the coping strategies driving deforestation,an approach they say hasn’t been tried before. Conservationists have always tried to ‘improve the livelihood of the farmers’, according to Andriamihaja. But farmers’ coping strategies have to do with long-term planning, not just securing the day-to-day food supply or planting specific crops. “This planning is not really yet considered as a means of helping the farmers [as well as] helping in conservation,” she says.

“It just triggered a new wave of deforestation”“The idea is to have the same price – and they can’t do it without a co-operative”

Bruno Ramamonjisoa, University of Antananarivo

A timely co-operative push

There’s another reason, aside from the “triple crisis”, which makes this a good moment to act.

The Malagasy Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Handicraft is in the process of revising the law that governs co-operatives, which can strengthen farmers’ negotiating power on cash crop prices.

Even before this process began, some farmers in the northeast were keen to form a co-operative in an attempt to even-out the playing field. “There is inequality because if a farmer doesn’t want to sell with the low price, they [traders] can go [to] another farmer,” explains Ramamonjisoa. “The idea is to have the same price – and they can’t do it without being in a co-operative.”

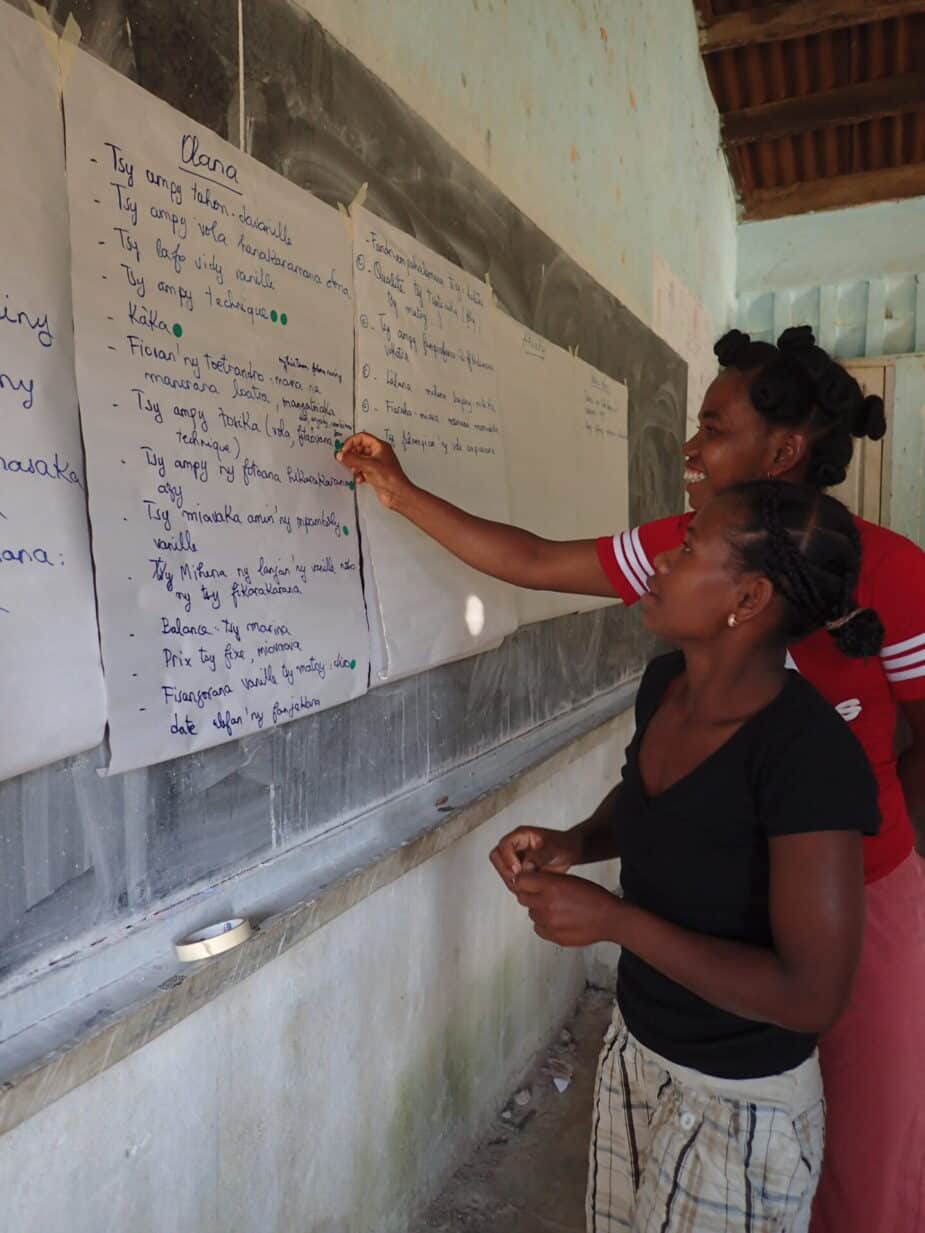

Picture 2:Workshop participants in Fizono village, watching a video where a representative of the Ministry of Trade and Consumption discusses co-operatives. Credit: O. Ravaka Andriamihaja

International exporting and importing companies also grab a big slice of the pie, bringing in their representatives to influence market regulation in the region. “They really have direct power on the village and the farmers,” says Andriamihaja.

As it stands, the law governs how co-operatives are organised. But it makes no mention of power relationships or influencing how the market is regulated. The revision opens a window of opportunity for the project to ensure that farmers have a say.

It’s easier said than done. In Madagascar, the government doesn’t typically consult interested groups before finalising a law, according to Ramamonjisoa. “My role is to see what is in the law and discuss with people at the ministry,” he says, “and to connect them with farmers”.

Both farmers and forests will benefit from co-operatives that promote fair prices and a stable income. If a farmer planting vanilla today is confident of getting a good price for the crop at harvest time three years later, that means less insecurity, says Andriamihaja –and less deforestation. “If we want them to follow or to adapt to regulation of deforestation, they need first to be able to plan their own life.”

A shared vision

The ultimate goal is to develop an inter-ministerial agreement that regulates deforestation more effectively. But first, the farmers need support to have a stronger voice when negotiating with regulators, conservationists and others touched by the vanilla trade.

The research team is helping the process along by organising a series of ten workshops. “Imagine if the farmer is talking with [a] Nestle representative, or to the ministries of envir

onment,” says Andriamihaja. “We want to hear from them, tapping on what they have lived for the last two years. What are their expectations? What do we do with this land?”

Nine workshops will take place in the district of Maroantsetra, bringing together farmers or their representatives from villages in the area to reach a shared understanding on key issues that affect them. The last single-day workshops will take place at the national level – one focusing on how to contribute to the revision of the Malagasy law on co-operatives, and the other on working together to avoid further agricultural expansion into forests. The team hopes the project will conclude with a signed agreement outlining the terms of that collaboration.

Picture 3: Workshop participants in Beanana village, ranking problems related to vanilla production and trade. Credit: O. Ravaka Andriamihaja

Time is tight – the national workshop is planned for early in the new year. The power dynamics around the vanilla trade will also be challenging for the team, which needs to find ways to help participants talk to each other on the same level. Then there’s the task of helping everyone understand how the different ‘worlds’ of farmers’ co-operatives and forest conservation link up.

For Ramamonjisoa, the biggest challenge is ensuring the project can be sustainable over the long-term. He believes the team is taking the right approach by making a point of listening to local people first, “to understand what they want to do, to analyse, and to suggest [how] to improve their initiative”.

It bodes well that relationships have already been built between researchers and participants who worked together in earlier phases of the project. Having on board key decision-makers from three Malagasy ministries – the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Ministry of Agriculture as well as the Ministry of Trade – also means the work is well placed to shape national policy.

The end may be about influence at the top, but the path to success starts with the farmers. “We cannot just come with regulation [against deforestation],” says Andriamihaja. “You have to help them first secure their future, their income, their life.”

Related Posts

The Green Vein: Agroecology Rising in West Africa

WOMEN EMPOWERED: Vital Work Made Visible

Sources

r4d project:

Managing Telecoupled Landscapes

Transformation Accelerating Initiative:

Managing telecoupled landscapes for the sustainable provision of ecosystem services and poverty alleviation

Credit title picture:

O. Ravaka Andriamihaja

About the author:

Anita Makri is a freelance editor/writer/producer based in London, UK.

Produced by:

Anita Makri